|

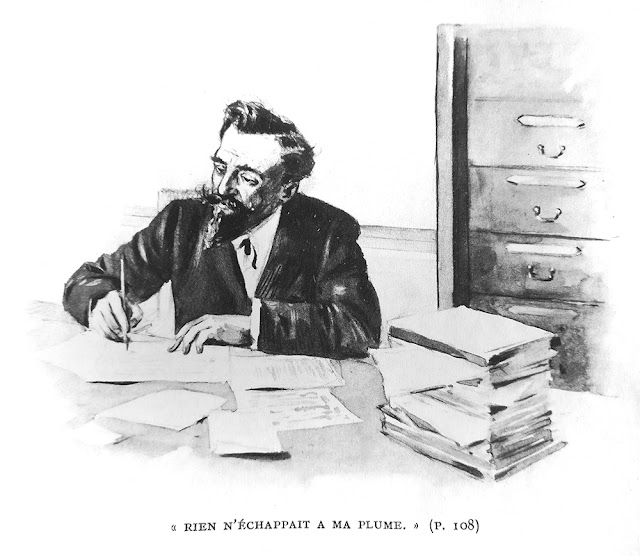

| Illustration by Louis Bailly, 1914 |

This episode, we join a cast of Conan Doyle’s literary heroes in his amusing short story, ‘A Literary Mosaic,’ also known as ‘Cyprian Overbeck Wells,’ which first appeared in December 1886.

You can read the story here: https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php/Cyprian_Overbeck_Wells._A_Literary_Mosaic

And you can listen to the episode here:

Synopsis

Smith is an aspiring young writer whose confidence in his

own abilities is unfortunately at odds with the opinions of publishers and

their editors. He is also currently suffering from a severe bout of writer’s

block. However, one evening, as he dozes by his fireside, following a

satisfying meal, a pint of beer, and a pipeful of tobacco, he mysteriously

finds himself in the company of some of English literature’s luminaries who

promptly embark on a collaborative literary adventure, both salutary and

improbably.

Writing and publication history

|

| You know what this is... |

Conan Doyle later wrote that “Girdlestone used to

come circling back with the precision of a homing pigeon.” He was more hurt

when the same occurred with Study which he felt “deserved a better fate.”

Smith says his story begins “about twenty minutes to ten on

the night of the fourth of June, eighteen hundred and eighty-six” which is as

fair an approximation of time of writing as any.

The story first appeared in The Boy’s Own Paper, Christmas

1886. The magazine had previously published Conan Doyle’s ‘An Exciting

Christmas Eve’ in December 1883 (Episode 9), and it was about to start serialising

‘Uncle Jeremy’s Household’ in January 1887 (Episode 17).

The story was later included in The Captain of the

Polestar and Other Tales (1890) as ‘Cyprian Overbeck Wells’ and now

subtitled ‘A Literary Mosaic.’ That collection was dedicated to Major-General

Alfred Wilks Drayson, President of the Portsmouth Literary and Scientific

Society, who made an introduction of Conan Doyle to The Boy’s Own Paper.

Conan Doyle had plans to reissue the story again c.1910 but

this was aborted. He intended to remove the references to James Payn, Walter

Besant, Ouida and Stevenson as ‘amongst the living’ as they had all then passed. The reference to

‘amongst the living is still’ in Tales of Twilight and the Unseen (1922)

as The Conan Doyle Stories (1929).

The narrator

Prior to Girdlestone, Conan Doyle had written a

novel, The Narrative of John Smith, which was lost in the post. He

rewrote it and it was eventually published in 2011. The name Smith might be a

call back to this novel. Conan Doyle also used the name Smith when playing

football in Southsea.

The experience of the “paper boomerangs” is very much Conan

Doyle’s own. There is also references to the small cylinders in which he used

to send manuscripts to publishers.

Smith’s crisis is both writer’s block and trying to find a

voice of his own. Much early Conan Doyle unconsciously mimics other authors,

with Girdlestone being an amalgam of sensationalist novelists such as

Collins and Dickens.

|

| Henry Highland Garnet |

Smith also says he wished to produce “some great work which

should single me out from the family of the Smiths, and render my name

immortal.” Conan Doyle felt the pressure of his famous Grandfather and Uncles,

especially Richard Doyle. He, like Smith, also sought his own independence, and

rejected the offer of money from his Catholic relatives to build his general

practice in Southsea.

Conan Doyle’s method may be that of Smith here, namely to

read extensively and seek inspiration that way. In Through the Magic Door,

Conan Doyle describes how each book “enfolds the concentrated essence of a man.

The personalities of the writers have faded into the thinnest shadows, as their

bodies into impalpable dust, yet here are their very spirits at your command.”

Forerunner – ‘Selecting a Ghost’

|

| Illustration by G. Dutriac, 1928 |

The principal authors

Daniel Defoe (1660-1731): Defoe’s section, and creation of

Cyprian Overbeck Wells, is a paraphrasing and pastiche of the opening of Robinson

Crusoe (1719). Defoe’s reference to how Lord Rochester’s word might “make

or mar” a young novelist, implies the pressure Conan Doyle felt under. As John

McVeogh pointed out, Defoe had a difficult relationship with Rochester’s works,

being attracted to it while being repelled by some of the moral philosophy.

McVeogh argues this is why Crusoe’s world-view is contradictory. John McVeogh,

Rochester and Defoe: A Study in Influence (1974) Studies in English

Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Summer, 1974), pp. 327-341.

Jonathan Swift (1667-1745): “Dean Swift” in reference to him

being an Anglican clergyman. Swift’s work is a pastiche of Gulliver’s

Travels (1726) which results in Cyprian Overbeck Wells being shipwrecked.

Swift’s tart exchange with Laurence Sterne alludes to Sterne’s A Sentimental

Journey (1768). Swift’s nautical detail amuses Smollett (see below) and

irritates Captain Marryat, author of Peter Simple (1834), Mr.

Midshipman Easy (1836) and the children’s classic, The Children of the

New Forest (1847)

Tobias Smollett (1721-71): Father of the picaresque novel

whose influence can be seen on Dickens and especially The Pickwick Papers.

Author of The Adventures of Roderick Random (1748), which is directly

referenced. Known for his absurdist comic scenes, which find their way into

Cyprian’s voyage. The character of Jebediah Anchorstock echoes Commodore Hawser

Trunnion in The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle (1751). Another absurdist character, Humphry

Clinker (The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, 1771) was well regarded by George Eliot and referenced in Middlemarch (1872).

|

| The St Louis Star, 4 Feb 1912 |

Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803-73): Diplomat, occultist, and

author of The Coming Race, which we discussed with Terror of Blue John

Gap in Episode 14, and most famously The Haunted and the Haunters, which

Conan Doyle regarded as the greatest ghost story written. Bulwer-Lytton’s Scott

pastiche can be seen in some of his historical novels, e.g. Harold, the Last

of the Saxon Kings (1848). He was teased mercilessly by contemporaries,

especially William Makepeace Thackeray. In ‘Mosaic,’ Conan Doyle briefly

confuses Bulwer-Lytton with his son who was Viceroy of India.

Who is missing?

|

| Charles Reade |

The San Francisco Chronicle (3 August 1890) observed that

‘Mosaic’ is “a fantasy in the style that Hawthorne was so fond of.” Certainly

multiple perspectives and consecutive narrators are a feature of his work.

However, Conan Doyle was not enamoured of Hawthorne who he found “too subtle,

too elusive, for effect.”

One might have expected Charles Reade, author of The

Cloister and the Hearth, to make an appearance. Another missing individual

was Mayne Reid, and one might have expected to hear from Marryat, both of whom

would have appealed to the readership of The Boy’s Own Paper.

Literary Parlour Games

Conan Doyle would contribute to Fate of Fenella (1891-92),

a collaborative novel in which each chapter was a different author, mostly alternating

between male and female. Other authors included Bram Stoker, Mrs. Trollope and

F. Anstey (author of Vice-Versa, the inspiration for ‘The Great

Keinplatz Experiment’).

In his spiritualist years, Conan Doyle claimed (or it was

claimed of him) to be in contact with deceased authors, among them Dickens,

Tolstoy and Thackeray. On the material plane, he finished Grant Allen’s novel

Hilda Wade on the author’s death-bed instructions.

Next time on Doings of Doyle

We are joined by Linda Bailey and Isabella Follath, writer and illustrator respectively of Arthur Who Wrote Sherlock, a new children’s biography of Conan Doyle.

Comments

Post a Comment