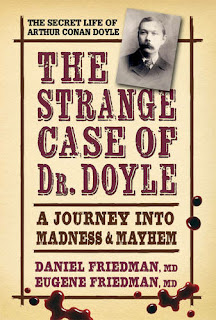

A Review and Refutation of

The Strange Case of

Dr. Doyle: A Journey into Madness & Mayhem

by Daniel Friedman, M.D. And Eugene Friedman, M.D.

(Square One Publishers, New York, 2015)

by Paul M. Chapman

On Wednesday 19th April 1905 a small but distinguished group of members of 'Our Society', an exclusive dining and discussion coterie known popularly as the Crimes Club, met for a guided tour of the Jack the Ripper murder sites in the East End of London. The tour was led by Dr Frederick Gordon Brown, the City of London Police Surgeon, who had examined the body of Ripper victim Catherine Eddowes in situ shortly after her murder on 30th September 1888, and then conducted the post-mortem. The tour members included the lawyer Samuel Ingleby Oddie, literary scholar John Churton Collins, the actor and true-crime aficionado H.B. Irving (Sir Henry's son), Dr Herbert Crosse and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

In The Strange Case of Dr. Doyle (henceforward The Strange Case), father-and-son writing team Daniel and Eugene Friedman make this tour the starting point for their joint study of Jack the Ripper and Arthur Conan Doyle. However, rather than using this historically-documented event itself, they instead substitute a 'fictionalized' account in which a version of Doyle himself leads a group of 'fictionalized surrogates' around the Ripper sites on 3rd October 1910. And herein lies the first of the many problems with this highly problematic book. On that specific date Conan Doyle was indeed visiting London, in order to deliver a talk entitled 'The Romance of Medicine' at St Mary's Hospital Medical School in Paddington (he did not at this time, or indeed ever, have a 'Kensington home', (1) as the Friedmans claim). It seems highly unlikely that he would have had the time to lead a criminological jaunt around the East End, lasting from 8am to 6.30pm, on the same day. Surely it would have been wiser for the authors to have chosen a day when Conan Doyle's itinerary was unknown?Structurally, this fictitious Ripper tour storyline runs alongside an ostensibly factual biography following Doyle's life until the publication of A Study in Scarlet in 1887. The book's chapters alternate between these two disparate narratives (which are differentiated by variant fonts) in a way designed deliberately to conflate them, and in doing so, to disorientate the reader.

In order (hopefully) to clarify matters for the purposes of this review, the 'real' historically-attested Arthur Conan Doyle will be designated throughout as Conan Doyle; the Friedmans' biographical version will be Doyle, and their 'fictionalized' tour leader, Dr. Doyle.

When discussing the influence of Doyle's celebrated Edinburgh medical tutor, Joseph Bell, the authors comment that 'Among other things, Doyle learned from Bell the power of sleight of hand'. (2) And - as if to prove a point - The Strange Case is abundant with literary sleights of hand. The picture of Arthur Conan Doyle presented in the fictional Ripper tour chapters blends together with that of the biographical, in an attempt to persuade the reader to accept the viability of the overwhelmingly negative portrayal of him that the Friedmans have concocted.

This is confounding enough in the avowedly 'fictionalized' chapters, in which a bumptious pseudo-Doyle harangues his tour guests and makes himself generally disagreeable. This unappealing caricature totally oversteps the mark when discussing Ripper victim Elizabeth Stride's use of cashew nuts to sweeten her breath. In a gross jest he says to his tour party; 'Perhaps I shall go out and buy some cachous for Mrs Doyle. Her breath is a bit stale. Ha! Ha!' (3) Never mind the sheer vulgarity and unforgivable breach of etiquette represented by this outburst, Arthur idealised Jean, Lady Conan Doyle. He would never have been such an ungallant boor, under any circumstance. Note, also, that grating 'Ha! Ha!'; it's leading somewhere, as are the Americanisms with which this coarse imposter punctuates his speech: 'fall' for 'autumn'; 'sidewalk' for 'pavement'; 'cute', and even (in 1910?) 'Go figure'!When it comes to the supposedly factual biography, the astute reader will soon detect a carefully-constructed skewed portrait of its subject. The popularly-accepted personification of Arthur Conan Doyle is of a bluff, hearty, sports-loving everyman type, with something of the sharp brain of a Sherlock Holmes, which was blunted when it came to the issues of Spiritualism and fairy photography. The Doyle (or should that be Doyles?) presented in The Strange Case cuts an altogether more sinister figure, given to blind egotism, paranoia, and a taste for violence and deceit. All apparently backed by evidence.

The real Conan Doyle was certainly a more complex and

ambiguous character than popular legend would suggest. But the Friedmans'

determination to paint an overwhelmingly dark picture tempts them down some

methodologically questionable paths, as, for instance, when they allege one

particularly anti-social escapade on the nineteen-year-old Doyle's part, after

he had become enamoured of a new toy – a powerful water launcher known as the

'Lady Teazer Torpedo'.

According to their version of events he bought himself one on 23rd May 1878 at a shop in Piccadilly Circus. He then ambushed his first victim:

' … a beautiful young lady exiting her carriage. Arthur struck with deadly accuracy and roared at the unpleasantness he had created for the now-waterlogged damsel. He then took off down the street with lightning speed, listening gleefully to the expletives being hurled at him by the lady's escort.' (4)

The source of this tale would seem to be a letter Conan Doyle wrote to his mother at the time (26th May 1878), which tells a rather different story:

'They have invented an atrocity called the “Lady Teazer torpedo”. This is a leaden bottle, like an artist's moist colour bottle, full of water. If you squeeze this a jet of water flies out and the great joke at night is to go along the street squirting at everybody's face, male or female. Everyone is armed with these things, and nobody escapes them. I was simply drenched last night; it is astonishing the good humour with which everyone allows it. I saw ladies stepping out of carriages to parties drenched and seeming to enjoy it highly.' (5)

In reality, then, he was a victim and observer of the effects of the 'Lady Teazer Torpedo', rather than being a phantom attacker himself!

Two years later, Conan Doyle served a term as surgeon on a whaling ship, the SS Hope, and actively participated in the expedition's hunting activities, allowing the Friedmans to weave a particularly bloody tapestry around their subject. During the gruesome business of seal culling he fell into the freezing ocean more than once, earning him the nickname 'The Great Northern Diver'. At one point, however, The Strange Case blends two separate incidents into one. After falling from an ice raft, and coming close to being crushed:' … a frightened Arthur was pulled to safety by two of the crew members. His mittens frozen solid, he thought he would have some fun by cutting off two hind flippers of the seals he had skinned, putting them on his hands as replacements.' (6)

This grotesque anecdote has its origins in a brief entry in Conan Doyle's Hope diary for 4th April 1880, in which he wrote:

'By the way as an instance of distraction of mind, after skinning a seal today I walked away with the two hind flippers in my hand, leaving my mittens on the ice.' (7)

No joke flipper-mittens, no ugly tomfoolery. Simply an exhausted absent-mindedness.

Following his Arctic adventure Conan Doyle returned to his medical assistantship (he was still a student at this time) with Dr. Reginald Ratcliff Hoare at Aston – not, as stated here, Aston Villa, which is actually the name of the local football team - in Birmingham. (English place-names suffer in this book; Pendle Hill is elevated to 'Pendle Mountain', Woolwich becomes 'Woolrich'.) Yet even here, the Friedmans claim, Doyle could not keep his penchant for malevolent pranks in check, and exploited Dr. Hoare's extensive patient roster to arrange a fake Lord Mayor's ball for Birmingham's social elite; a hoax which brought the police to Dr. Hoare's door, while his apprentice 'was likely somewhere in the shadows, watching the proceedings with delight'. (8) Curiously, this episode is not mentioned in any other biographical account and, as the authors provide no reference notes, its source is obscure.

The real Conan Doyle had a genuinely close relationship with Dr. Hoare and his wife, Amy, who stood almost in loco parentis to him. It seems highly unlikely therefore that he would endanger this for the sake of a foolish prank. If the police had been called to the Hoares' home under such circumstances he would have been dismissed in disgrace, whereas in actual fact his friendship with them lasted for years, during which time there is only one known documented disagreement between Conan Doyle and Dr. Hoare. This was alluded to in a letter he wrote to Hoare in 1882, in which he asked 'Do you still feel as bitter against me as you did that evening?' But it is clear from the letter's text that this was over something derogatory or underhand Conan Doyle was supposed to have said about Hoare, not about something he had done:'If you saw my mind the charge of saying a disloyal thing against you would seem ludicrous to you, as it does to me, and must do to any impartial friend.' (9)

So much for the Lord Mayor's ball that wasn't.

The authors of The Strange Case are at least right about one of Conan Doyle's character traits; his impulsiveness. In May 1882 he exchanged the comfort and security of his Birmingham internship for an ill-starred medical partnership in Plymouth with his old student acquaintance, George Turnavine Budd; an erratically brilliant showman-medic, who was also an unscrupulous charlatan. Predictably, the partnership soon foundered and Conan Doyle found himself starting afresh in Portsmouth. He arrived there on 24th June 1882, when, according to The Strange Case:

'He was dressed in the only clothing he had, a heavy tweed suit … Later that evening, he decided to take a walk through town. According to his account, he ended up walking right into the middle of a street fight around which a crowd of spectators had gathered.' (10)

The fracas apparently centred around 'a brawny drunk kicking his wife, who had a baby in her arms'. (11) Doyle tried to intercede on her behalf. The Strange Case says:

The observant reader will have noticed that the sartorially-challenged Doyle has suddenly acquired a frock coat and top hat, the reason being that the Friedmans have taken 'his account' of this fight from The Stark Munro Letters, Doyle's semi-autobiographical novel based on his experiences in Plymouth and Portsmouth/Southsea, first published in The Idler in 1894. They quote this source, as if it were established fact, several times throughout The Strange Case. (Hesketh Pearson did the same in his 1943 biography, Conan Doyle: His Life and Art.)'Of the experience, Doyle would write, “I found myself within a few hours of my entrance into this town, with my top hat down to my ears, my professional frock coat, and my kid gloves, fighting some low bruiser on a pedestal in one of the most public places, in the heart of a yelling and hostile mob!”' (12)

Conan Doyle actually did become involved in a Portsmouth street fight, but it was on the 28th June, four days after his arrival, as he recalled in a letter to his mother:

'I had a turn up with a tinker in the main street of the town on Coronation night and milled him to the delight of an enthusiastic mob. He had been kicking his wife, and caught me on the throat when I interfered.' (13)

Since the Friedmans' purpose in using this anecdote is to illustrate Doyle's supposed violent streak, it is unclear why they chose the fictional variant. Oddly enough, they neglect to mention an earlier similar incident from his student days, which is documented in his autobiography, Memories and Adventures (1924). In this case Conan Doyle became involved in an altercation outside a theatre with an off-duty soldier who had:

' … squeezed a girl up against the wall in such a way that she began to scream. As I was near them I asked the man to be more gentle, on which he dug his elbow with all his force into my ribs. He turned on me as he did so, and I hit him with both hands in the face.' (14)

Neither of these episodes provides unambiguous proof of an overtly aggressive persona. Both were defensive actions prompted by protective (one might even say chivalrous) instincts.

Naturally, there is even less regard for demonstrable fact during the 'fictionalized' Ripper tour. Although its route more or less faithfully follows the trail of the 'canonical' five victims (Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly), the conceit of allowing tour members to theorise independently confuses the overall picture, and errors creep in. For instance, at one point it is stated that Mary Kelly's rent-collector knew that she would be at home on the fateful 9th November 1888 because she had told him that 'she would be watching the scheduled Lord Mayor's Day procession from her window as it passed by her apartment'. (15) Highly unlikely, given that her poky single room – which could hardly be categorised as an 'apartment' – was down a dingy court leading from Dorset Street, one of London's most dangerous and disreputable thoroughfares.And then there are the anachronisms. During the course of their discussions Dr. Doyle and his tour guests openly debate the theories surrounding the alleged involvement of the Freemasons, the British Establishment and/or members of the Royal Household in the Ripper case. Apparently, the former heir presumptive to the British throne, Prince Albert Victor, who had died in 1892, had 'long been rumored to have been the Ripper'. (16) Not so. Not in 1910, as none of the outlandish and tedious conspiracy theories which link his name with Jack the Ripper emerged until the 1970s. In addition, the real Arthur Conan Doyle would have known that the Prince was the Duke of Clarence and Avondale, not, as Dr. Doyle states here, 'both Duke of Clarence and Duke of Avondale'. (17) Nor was Albert Victor 'Prince of Wales', as listed in the index; that was his father, Prince Albert Edward, later King Edward VII.

Next come the so-called 'Ripper letters', the torrent of crackpot and malicious correspondence sent to various public figures and organisations throughout the time of the Ripper scare. One of the most notorious of these was received by George Lusk, the chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, on 16th October 1888. Addressed 'From hell' and accompanied by part of a human kidney, it was, understandably, treated with a degree of seriousness, although it has never been proved that the organ sample came from Catherine Eddowes' body, as the writer claimed (and Dr. Doyle here asserts). The letter's text contains the words 'Sor', for 'Sir', and 'mishter', for 'mister', in an obvious approximation of a mock music-hall Irish accent. Yet the Scots-Irish Dr Doyle recites it in 'a Cockney accent' (18) and then engages in an absurd and (unintentionally?) funny debate over the possible implications of the word 'mishter'.

Earlier on in the tour Dr. Doyle produces another letter, dated 17th September 1888, addressed 'Dear Boss' and signed 'Jack the Ripper'. But this is not the historically infamous 'Dear Boss' letter, dated 25th September 1888, which gave the murderer his Americanisms, his 'ha ha' catchphrase and his immortal sobriquet. That actual document is referenced later, but, crucially, without its date, thus disguising the authors' sleight of hand through which Dr. Doyle is seemingly in possession of an earlier communication from the same source. At no point in The Strange Case is it made clear that the 17th September letter has been concocted especially for this 'fictionalized' exploration of Whitechapel and its environs.

It is on record that Arthur Conan Doyle saw and handled the real 'Dear Boss' letter when he visited Scotland Yard's private 'Black Museum' on 10th December 1892, in company with Jerome K. Jerome and E.W. Hornung. This letter, together with some other documents relating to the Ripper and Crippen cases, later went missing from the archive (to be returned anonymously in November 1987). The Strange Case slyly asserts that 'It was commonly assumed that the entire Ripper letter collection had disappeared around the time of Doyle's visit'. (19) The implication is clear. Doyle must have been up to his pranks again. Yet he could hardly have lifted 'the entire Ripper letter collection', which comprised some hundreds of documents, single-handedly! (Perhaps the great humorist Jerome, and Hornung – the creator of gentleman thief A.J. Raffles - were also in on the act?) Furthermore, if the 'Dear Boss' letter disappeared concurrently with the Crippen material this could not have been 'around the time of Doyle's visit', as the Crippen case dated from 1910. (Crippen's trial was the sensation of the season that autumn, and Conan Doyle even attended its opening day, 18th October.)Where, then, is all this leading? To the Friedmans' inevitable conclusion, of course:

'Realizing that these troublesome inclinations existed in a young man of great strength, speed, agility and stamina was a turning point for us. It was the moment we realized that Arthur Conan Doyle might be Jack the Ripper.' (20)

Take note of that qualifying 'might be'. The concluding 'Afterword' of The Strange Case is peppered with that phrase, or variants upon it.

And why would Conan Doyle commit these crimes? Apparently, that leads us back to his father, Charles Altamont Doyle, an unworldly artist who suffered from alcoholism and its attendant physical and mental consequences for much of his adult life, and was institutionalised in a series of asylums from 1879 until his death in 1893.But – as if his well-documented alcoholism, epilepsy and dementia were not enough – the Doctors Friedman (they are both M.D.s, as the book's cover clearly tells us) speculate that he possibly also suffered from syphilis. From their understanding of some of his medical records, he may have exhibited the loss of knee-jerk reflex, one of the indicators of tabes dorsalis, a degeneration of the nerves of the spinal cord attendant upon syphilis.

In 1885 Arthur Conan Doyle had written his M.D. thesis on tabes dorsalis ('Upon the Vasomotor Changes in Tabes Dorsalis and On the Influence Which is Exerted by the Sympathetic Nervous System in That Disease'). Given this, the Friedmans believe, he may have noticed the symptoms in his father, thus sparking vengeful thoughts towards the prostitutes from whom Charles had (presumably) caught the disease. Unfortunately for this theory it fails to take into account that Charles was a well-known figure on the Edinburgh drinking circuit and that there is no known evidence, either circumstantial or documentary, that he consorted with prostitutes.

Strangely enough, the Friedmans' plotline harks back to the first full-length study of the Ripper case, The Mystery of Jack the Ripper by Leonard Matters, published in 1929, in which the mysterious 'Dr Stanley' becomes Jack the Ripper in order to avenge his brilliant medical student son who has died of syphilis contracted from Mary Kelly. The Strange Case reverses the roles – here the son is the avenger – and adds an additional twist, in which Arthur's vengeful spirit is further fuelled by his recurrent 'facial neuralgia' (which, so the theory runs, he may have self-diagnosed as a symptom of congenital syphilis) and - an entirely speculative - propensity to the delusional condition paranoia vera.

Conan Doyle's M.D. thesis, despite its ponderous scientific title, is almost as much a meditation upon the artistic and cultural history and significance of tabes dorsalis and syphilis as it is a medical investigation of the condition itself. 'In many cases [the sufferer] is of that swarthy neurotic type which furnishes the world with an undue proportion of poets, musicians and madmen', (21) he states. Therein lay the subject's real attraction to him. He was, after all, a writer (something the medically-minded Friedmans often seem to forget) born into a notable artistic family. Medicine was his profession, and one he took seriously, but it was not his primary calling.

As for his supposed hatred of prostitutes, in June 1883 Conan Doyle did become embroiled in a public controversy when he objected in print to the suspension of the 1864 Contagious Diseases Act, which had allowed for the detention of prostitutes on medical grounds, and some of his language was undeniably intemperate and provocative. But he was not driven by a deep-seated vendetta against the prostitutes themselves. He was speaking as a doctor in Portsmouth, one of England's principal garrison towns, where the social and medical problems represented by the sex trade were inevitably exacerbated. He also had an ulterior motive, as becomes clear in a contemporary letter to his mother (15th June 1883):

'I hope you saw the little shindy which I kicked up in the D.T. Such a lot of letters from private people I have had since, and pamphlets galore – most of them complimentary and a few the reverse. There is a leader on me in the “Medical Press” of Wednesday and I have no doubt the Lancet & British Medical will allude to it, so that I have had a stir up all round. It has got my name known locally anyhow – I enclose a sample of my correspondence. It was a happy thought of mine, wasn't it?' (22)

Self-publicity using one's own name is hardly the hallmark of a serial killer in the making!

So much for 'motive'. The 'evidence' is even more nebulous. Doyle cannot be placed in the East End of London in the autumn of 1888, and he certainly did not possess the Ripper's apparent knowledge of the rat-runs of Whitechapel and Spitalfields. (The Strange Case states, with rather more imagination than proof, that he spent a 'few weeks down at the East End docks in the summer of 1878'. (23) Indeed, his knowledge of London in the late 1880s was demonstrably rudimentary, and gleaned mainly from occasional visits to his relatives in Maida Vale in West London and the consultation of street maps. Thus the city, as it appears in A Study in Scarlet, written in 1886, has more in common with Doyle's native Edinburgh than with the capital city of the British Empire.The Friedmans' entire argument is, in fact, predicated upon a heady blend of inference, supposition and misdirection, which reaches a particular nadir when they attempt to analyse the self-caricature drawn by Conan Doyle upon achieving his MB CM (Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery) degree, which he captioned 'Licensed to kill':

'Of course, his cartoon celebrating the attainment of his medical diploma, with its caption “Licensed to kill”, may be the clearest example of a merciless soul.' (24)

Or, it could, of course, be an example of youthful exuberance and the sort of gallows humour for which medical students are well renowned.

As previously stated, it is difficult to track down the Friedmans' actual sources for some of the information in The Strange Case, as they fail to provide any reference notes. The so-called Annotated Bibliography is certainly eclectic, but it is essentially an eccentrically-organised and confusing grab-bag of works consulted (it would seem that Arthur Conan Doyle wrote something called The Captain and the Polestar, and that there is a biography of John Hill Burton called The Book-Hunter). For writers who claim to have conducted 'in-depth research to see if anything of relevance might have been missed' (25) there are some glaring omissions. On Conan Doyle they neglect to mention some of the most important landmark studies: The Quest for Sherlock Holmes by Owen Dudley Edwards, A Study in Southsea by Geoffrey Stavert, Out of the Shadows by Georgina Doyle, and Conan Doyle, Detective by Peter Costello. Although many books on Jack the Ripper are generally best ignored, The Complete Jack the Ripper by Donald Rumbelow, The Complete History of Jack the Ripper by Philip Sugden, Jack the Ripper: The Facts by Paul Begg, and The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook by Stewart P. Evans and Keith Skinner are all essential. Yet none are listed here.

Arthur Conan Doyle may have had his faults, but he was not Jack the Ripper, and students of

both individuals and the cultural phenomena surrounding them will learn little from

this depressingly disingenuous and attention-seeking book, which belongs firmly

in the dubious field of 'faction' or 'infotainment'. The trouble is that it is

neither reliably informative nor particularly entertaining. If the Conan Doyle

Estate Ltd are really serious about protecting Sir Arthur's legacy, they would

be better advised to put their energies into loudly and unequivocally

condemning this sort of ill-informed and mischievous attack upon his memory,

rather than spending their time chasing the ever-diminishing returns of his

Sherlockian legacy.

Paul M. Chapman, 12th April 2021

(With many thanks to Teresa Dudley, for helpful suggestions, text checking, and for aiding in my differentiation of 'Doyles'!)

Notes

(1) Daniel Friedman, M.D. and Eugene Friedman, M.D., The Strange Case of Dr. Doyle: A Journey

Into Madness & Mayhem (Square One Publishers, New York, 2015), p.298.

(2) Ibid., p.108.

(3) Ibid., p.131.

(4) Ibid., p.140.

(5) Jon Lellenberg, Daniel Stashower and Charles Foley

(Eds.), Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in

Letters (HarperPress, London, 2007),

pp.102-103.

(6) Op. Cit. (1), p.153.

(7) Arthur Conan Doyle (Ed. by Jon Lellenberg and Daniel

Stashower), 'Dangerous Work' Diary of an Arctic Adventure (The

British Library, 2012), p.240.

(8) Op. Cit. (1),

p.162.

(9) Op. Cit. (4),

p.181.

(10) Op. Cit. (1),

p.251.

(11) Ibid.

(12) Ibid., pp.

251-252.

(13) Op. Cit. (4),

p.162.

(14) Arthur Conan Doyle, Memories

and Adventures (Oxford University Press, 1989), p.33.

(15) Op. Cit. (1),

p.237.

(16) Ibid., p.245.

(17) Ibid.

(18) Ibid., p.179.

(19) Ibid., p.307.

(20) Ibid., p.309.

(21) Arthur Conan Doyle (Ed. by Owen Dudley Edwards), The Edinburgh Stories (Polygon Books,

1981), p.82.

(22) Op. Cit. (4),

pp.202-203.

(23) Op. Cit. (1),

p.140.

(24) Ibid., p.309.

(25) Ibid., p.304.

Comment submitted on email from Donald Pollock: I enjoyed Paul Chapman's review of the book 'The Strange Case of Dr. Doyle', and I wanted to recommend the review by Jon Lellenberg of the book, which appeared in 'The Saturday Review of Literature', #4, 2016, pages 21-23.

ReplyDelete